Capacity and Consent

1. Consent in Relation to Safeguarding

Effective safeguarding comes from agencies working together, sharing proportionate and timely information.

It is important to understand consent and information sharing in the spirit of making safeguarding personal.

The MSP approach is about ensuring adults exercise their right to make decisions about their own lives. Acting without involving people (at risk) or seeking their consent has the potential to further disempower them. Interventions should be negotiated and communicated.

If the person (at risk) is not the person raising the safeguarding concern, wherever possible every effort should be made to seek their views and agreement, unless doing so is likely to increase the risk to the adult or put others at risk. |

Empowering adults involves a proactive approach to seeking consent and maximising their involvement in decisions about their care, safety and protection, and this includes decisions regarding whether to raise a safeguarding concern.

All interventions must take into account the capacity of the adult to make informed choices and specifically the adult's ability to understand the implications of their situation and to take action themselves (or with support) to prevent abuse, and to participate to the fullest extent possible in decision-making about safeguarding interventions.

Adults may have reservations about their concerns being raised as a safeguarding matter. For example, they may be unduly influenced, coerced or intimidated by another person, they may be frightened of reprisals, they may fear losing control, they may not trust social services or other partners, or they may fear that their relationship with the person (subject of the abuse) will be damaged. Reassurance and appropriate support may help to change their view on whether it is best to share information. Staff should consider the following and:

- Explore the reasons for the adult's objections – what are they worried about?

- Explain the concern and why you think it is important to share the information;

- Tell the adult with whom you may be sharing the information with and why;

- Explain the benefits to them, or others, of sharing information – could they access better help and support?

- Discuss the consequences of not sharing the information – could someone come to harm?

- Reassure them that the information will not be shared with anyone who does not need to know;

- Offer the reassurance that support is available to them.

Care Act UK guidance (also cited in our procedures):

ADASS Duty to carry out safeguarding adult enquiries advice note 2019: Making Safeguarding Personal does not mean 'walking away' if a person declines safeguarding support and/or a (CA S42) enquiry. That is not the end of the matter. Empowerment must be balanced for example, with Duty of Care and the principles of the Human Rights Act (1998) and of the Mental Capacity Act (2005). People must not simply be abandoned in situations where, for example, there is significant risk and support is declined and/or coercion is a factor. |

See Information Sharing Policy

For further reading, see the Safeguarding Partnership Board website:

Information Sharing Guidance – Vulnerable Adults

SPB Information Sharing Protocol2. Capacity and Safeguarding

Capacity refers to the ability to make a decision about a particular matter at the time the decision is needed. It is always important to establish the capacity of an adult who is at risk of abuse or neglect, should there be concerns over their ability to give informed consent to:

- Plan interventions and decisions about their safety;

- Add to a safeguarding plan and how risks will be managed to prevent future harm.

It is a misconception that adult safeguarding procedures (in Jersey) only relate to people who lack capacity to consent to a safeguarding intervention. Safeguarding covers a wide range of adults with care and support needs, including people who may lack capacity in respect of specific decisions about risk.

Adult safeguarding also involves working with people who DO have capacity to make relevant decisions. It is important to ensure that they are not excluded from adult safeguarding. Capacity should not be viewed as a barrier to safeguarding however, the approach must recognise an individual's wishes, feelings and rights. |

If a person cannot make a specific decision, it does not mean that what they want and choose for themselves is to be overridden. It is important to remember capacity is decision specific and time specific. Whilst a person might not be able to make some decisions about care/treatment/support, they may be able to make others.

A capacitated refusal (for a safeguarding intervention) is not to be seen as the end of the concern, as this may require ongoing risk management, monitoring, or changes to care and support. Further multi-disciplinary discussions and interventions may need to continue. |

All staff must familiarise themselves and stay updated in respect of the Capacity and Self Determination Law (Jersey) 2016 (CSDL). Capacity, lack of capacity and working out what is in the person's Best Interest (when they lack capacity) is defined by the CSDL and the associated code of practice.

Notably these FIVE CSDL principles must be considered in relation to safeguarding:

- A person must be assumed to have capacity unless it is established that (s)he lacks capacity;

- A person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision unless all practicable steps to help him (her) to do so have been taken without success;

- A person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision merely because (s)he makes an unwise decision;

- An act done, or decision made, under this Act for or on behalf of a person who lacks capacity must be done, or made, in her (his) best interests;

- Before the act is done, or the decision is made, regard must be had to whether the purpose for which it is needed can be as effectively achieved in a way that is less restrictive of the person's rights and freedom of action.

Regarding principle 2: People need to be provided with all practicable support to enable them to make their own decision before it can be concluded that they lack capacity regarding the decision and a best interests process is entered into. This may be achieved in a variety of ways such as: how we provide information (both format and content); more education; interpreters; communication aids; time of day; the help of a family member or friend (if not implicated, or subject of abuse), or an advocate or representative. A person need only to understand the main points of information to make that decision.

Regarding principle 5: UK research has found that staff are not routinely compliant with this principle. The decision or intervention that is least restrictive of rights and freedoms is likely to be the most empowering.3. Capacity, Consent and wilful Neglect

The possession of functional decision-making capacity is only one of the three elements of valid consent. Valid consent must be:

- Informed, with a person having appropriate information;

- Capacitous, with a person having decision-making ability;

- Voluntary, with a person being free from coercion or undue influence.

All three elements must be present for a person to make an autonomous decision to give valid consent.

The Capacity and Self Determination Law (Jersey) 2016 (CSDL) only allows decisions to be made on behalf of a person who lacks capacity, to make the decision for themselves, under the best interests process by a decision-maker. Where adults retain capacity but their ability to promote their own interests is seriously compromised, such as being coerced, the CSDL cannot be used. However, controlling or coercive behaviour should be dealt with as part of safeguarding and public protection procedures. In such instances an application could be considered for the Court (Jersey) to exercise its inherent jurisdiction.

The Court's inherent jurisdiction is, in part, aimed at enhancing or liberating the autonomy of a vulnerable adult whose decision-making ability is compromised by a reason other than capacity. This can include being:

- Under constraint;

- Subject to coercion or undue influence;

- Deprived of the ability to make the relevant decision or disabled from making a free choice for some other reason;

- Prevented from giving or expressing valid consent.

The purpose of applying inherent jurisdiction should be protective in relation to adults in vulnerable circumstances. The Court will always avoid undermining the five core principles in Article 3 of the CSDL. They will give considerable weight to the principle that a person can make unwise decisions.

There is no specific definition of what constitutes vulnerable in such cases. The inherent jurisdiction is not confined to vulnerable adults. Equally adults at risk of abuse and neglect do not automatically come under the definition of vulnerable. There is a risk that professionals involved in the care and treatment of a person may feel drawn towards an outcome that is more protective and in certain circumstances fail to carry out an assessment that is detached and objective. The Court will critically review evidence for the 'protective imperative' to ensure that the application of inherent jurisdiction does not raise the spectre of judicial paternalism. Therefore, an application for the use of inherent jurisdiction is normally restricted in scope to an autonomy promoting or defending role.

Professionals must consider that the use of inherent jurisdiction would risk breaching Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), a person's right to respect for private and family life. Legal advice should be sought regarding the appropriateness of asking the Court to consider exercising its inherent jurisdiction on human rights grounds. The purpose of the Court using inherent jurisdiction is not to overrule the wishes of an adult with capacity, but to ensure that the adult is making decisions freely.

Wilful neglect is where a person ill-treats or wilfully neglects any person they have the care of, by virtue of being paid to provide social care or health care. It should be noted that any neglect should be 'wilful' and that ill-treatment requires a deliberate act or action that is reckless. Genuine errors or accidents are not within the scope of the offence.

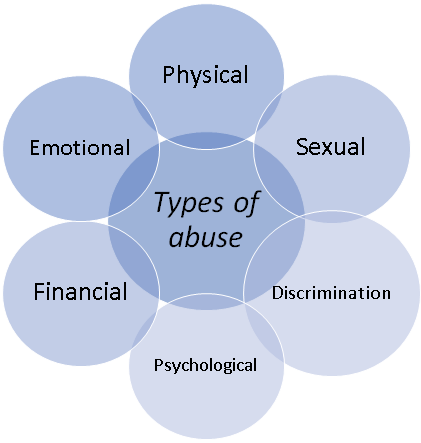

There is no definition of ill-treatment or neglect within the Law so everyday meanings provide definition. The meaning of ill-treatment relies upon definitions of types of abuse which include the following areas:

The offence of wilful neglect applies to the care and treatment of people, in care homes, provided with home care and in supported living arrangements. The offence carries the legal sanctions of both fines and imprisonment for any person found guilty of the crime.

4. Human Rights and Safeguarding

Human Rights (Jersey) Law 2000 has informed the context of this adult safeguarding policy.

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), details a number of rights, which the Human Rights (Jersey) Law 2000 makes directly enforceable in the Courts in Jersey.

The Human Rights (Jersey Law) 2000 makes it unlawful for a public authority to act in a way which is incompatible with a Convention right. In this article "public authority "includes any person whose functions are of a public nature." This includes Health and Community Services, the Police and anyone exercising a public function. This is broad in Jersey due to the nature of funding for services. For example, long-term care benefit paid to a private home means the private care provider is carrying out a public function. An 'act' includes a failure to act.

Public authorities need to be guided by the ECHR and the Human Rights (Jersey) Law 2000.

When working with Adults at Risk, the following rights are often engaged:

- Everyone has the right to live their lives free from inhumane and degrading treatment or punishment, which may result from intimidation, oppression or the infliction of serious physical, sexual, emotional or mental harm;

- Everyone has the right to respect for family life and privacy;

- Everyone is entitled to the peaceful enjoyment of possessions and home;

- Everyone has the right to the protection of the law and to have their civil rights determined, or their compulsory detention reviewed, by an independent and impartial court or tribunal.

For further details on Human Rights, see the Citizens Advice.

5. Significant Restrictions on Liberty (SRoL)

There are times when a person's care includes ongoing restrictions, which may impact on the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) Article 5 (right to liberty). In some jurisdictions, Article 5 of the ECHR talks of 'deprivation' of liberty. In Jersey, significant restriction on liberty (SRoL) should be taken to have the same meaning.

Where a person has capacity, they can consent to restrictions that are applied to them as a feature of care and treatment. A person who lacks capacity does not lose their right to liberty simply because they may no longer be able to consent to their care and treatment in a place, such as a care home or hospital. A person's human rights do not change even if the decision or act is taken to keep a person who lacks capacity to make the decision safe.

The SRoL process is a safeguard that allows significant restrictions on liberty to be made lawful through an authorisation process. Authorisations are designed to prevent arbitrary decisions that deprive a person of their liberty. |

The term 'authorisation' for a significant restriction on liberty means that the manager of a relevant place, such as a care home or hospital, must seek authorisation from the Minister in order to be able lawfully to restrict a person's liberty. Before giving an authorisation, the Minister must be satisfied that the person is unable to give consent about residence or treatment in the setting because they suffer from an impairment or disturbance in the functioning of the mind or brain, which prevents them making the decision.

It is important to realise significant restrictions on liberty (SRoL) must be legally authorised, as any human rights interference 'must be in accordance with a procedure prescribed by law'. By using this process, the Minister can ensure that independent assessments check the details and manner of the person's care. This is to ensure that the care is in the person's best interests and limits their rights and freedom of action as little as possible. If there are concerns regarding overly restrictive matters, conditions would be set to make arrangements to change these parts of the care.

Authorisations can only be made in relation to people aged 16 and over. If the issue of restricting the liberty of a person under the age of 16 arises, other safeguards must be considered. This would be under the inherent jurisdiction of the Court

For more information see chapter 11 of the Capacity and Self-Determination (Jersey) Law 2016 Code of Practice.6. Advocacy

The Capacity and Self Determination (Jersey) Law 2016 introduced the role of the Independent Capacity Advocate (ICA). The Capacity and Self Determination Law sets out the ICA roles and functions.

The role of the ICA is to support a person who lacks capacity, who has no other supports (such as friends or family) with three types of decision:

- Serious medical treatment;

- Long-term change in accommodation;

- Imposing significant restriction on liberty.

The ICA is a statutory role and has powers under the law to challenge decisions on behalf of a person lacking capacity. Once the decision is made the statutory role of the ICA ends, however, general advocacy may still be offered.

6.1. Role of ICA

The ICA role is to support and represent the person in the decision-making process. Essentially, they make sure that the person's rights and wishes are taken into account and the Capacity and Self Determination (Jersey) Law2016 is being followed.

6.2. Why is the ICA role important?

ICAs are a legal safeguard for people who lack capacity to make some important decisions, including making decisions about where they live and about serious medical treatment options.

6.3. How ICA works

1. Gathering information

- Meet and interview the person (in private if possible);

- Examine relevant health and social care records;

- Get the views of professionals and paid workers;

- Get the views of anybody else who can give information about the wishes and feelings, beliefs or values of the person;

- Find out other information which may be relevant to the decision.

2. Evaluating information

- Check that the person has been supported to be involved in the decision;

- Try to work out what the person's wishes and feelings would be if they had capacity to make the decision and what values and beliefs would influence this;

- Make sure that different options have been considered;

- Decide whether to ask for a second medical opinion where it is a serious medical treatment decision.

3. Making representations

ICAs should raise any issues and concerns with the decision maker. This could be done verbally or in writing. ICAs are required to produce a report for the person who instructed them. In most cases this should be provided to the decision maker before the decision is made.

People who instruct ICAs must pay attention to any issues raised by the ICA in making their decision.

4. Challenging decisions

In many cases ICAs will be able to resolve any concerns they have with the decision maker before the decision is made. Where this has not been possible ICAs may formally challenge the decision-making process. They can use local complaint procedures or try to get the matter looked at by the Royal Court.

6.4. Who should get an ICA?

An independent capacity advocate (ICA) must be instructed for people in the following circumstances:

- The person is aged 16 or over;

- A decision needs to be made about either a long-term change in accommodation or serious medical treatment;

- The person lacks capacity to make that decision, and there is no one independent of services, such as a family member or friend, who is "appropriate to consult".

6.5 ICA and Significant Restrictions on Liberty (SROL)

ICAs must be instructed for people who are being assessed as to whether they are currently being, or should be deprived of their liberty, where there is no-one "appropriate to consult".

The role of ICA is a statutory role, linked to three types of decision. Non-statutory advocacy is still available for other circumstances. Support from advocacy services can still be provided to people for other decisions concerning care Reviews or Adult Protection/Safeguarding.

In adult protection or Safeguarding cases, an ICA may be instructed even where family members or others are available to be consulted.

7. Advocacy and Adult Safeguarding

In making decisions about a person's care and support, Health and Community Services (HCS) Safeguarding Adult Team (SAT) must consider whether a person would have 'substantial difficulty' being involved. Substantial difficulty would be if the person has problems with one or more of these:

- Understanding information about the decisions;

- Remembering information;

- Using the information to be involved in the decisions;

- Being able to tell people your views, wishes and feeling.

The HCS then needs to consider whether the person has an 'appropriate individual' to support them. This is someone who will be available and able to support the person. It can be a family member or a friend but will not be someone the person requests should not be involved.

If the HCS SAT decide that the person has substantial difficulty being involved and does not have an appropriate individual to them, then an Advocacy worker should be considered.

For Advocacy and ICA advice in Jersey please see My VOICE website

Capacity and safeguarding interventions will be covered further in the Adult Safeguarding Procedures.