Making Safeguarding Personal - A Toolkit & Practitioner Guide

1. Introduction

'Making Safeguarding Personal' (MSP) is an approach to Safeguarding that aims to ensure that the Person (adult at risk) and/or their advocate in relation to the safeguarding enquiry, are fully engaged and consulted throughout and that their wishes and views are central to the final outcomes as far as is possible. The person has rights under the adult safeguarding policy and procedures and the Capacity & Self Determination Law (2016) to be supported and represented by an independent advocate when certain conditions are met. The person needs to feel as empowered as possible, to have choice and control throughout the safeguarding intervention.

For many practitioners carrying out your role, you will already be working hard to find out what's important to the people involved, so that the actions and interventions that are put into place are welcomed by them and viewed as constructive and helpful.

The introduction of 'Making Safeguarding Personal' requires that whilst working closely with the individual who has been abused or neglected and/or their advocate in order to understand what they want from the process, you must also carefully record their wishes at the outset and on an on-going basis. This enables everyone to clearly see at any stage throughout the enquiry what progress is being made relating to the desired outcomes, or if a change to these has been needed, why and when it took place.

At the end of the enquiry you are also required to gain feedback from the individual or their advocate about their experiences throughout - and their overall satisfaction establishing if a difference has been made.

To support you in this we have produced this 'Making Safeguarding Personal' guide and toolkit which covers:

- The principles of 'Making Safeguarding Personal';

- When and how to apply 'Making Safeguarding Personal';

- The importance of meeting the person concerned and/or their advocate;

- Conversations to find out what the person wants to happen;

- Capturing and recording information about their wishes;

- Recording and evaluating the desired outcomes at the different stages of the intervention.

This is supplementary guide and for use alongside the SPB Adult Safeguarding Policy & Procedures. This guide is not a replacement for the above Policy and Procedures. This is aide to help put 'Making Safeguarding Personal' into practice.

Six Principles of Adult Safeguarding

These principles apply to all sectors and should inform the ways in which professionals and other staff work with adults (Care Act, 2014).

2. The Principles of 'Making Safeguarding Personal'

In the past, people involved in adult safeguarding processes have said they can sometimes feel they have little control in respect of what's happening to them; are not involved in discussions; are rushed to make decisions and have little say over outcomes. 'Making Safeguarding Personal' therefore promotes a shift in culture and practice, which ensures that safeguarding is more effective from the perspective of the person involved in the enquiry.

MSP is about having meaningful conversations with people (adults at risk), seeing them as experts in their own lives and working successfully alongside them all the way through the safeguarding intervention, so that at the end they feel they have been fully involved and are satisfied by the outcome, as far as is possible. It is also about collecting and recording information that demonstrates the impact on the person's life and the positive difference it has made.

'MSP is a shift from a process supported by conversations to a series of conversations supported by a process' Making Safeguarding Personal Guide 2015' Local Government Association & Directors of Adult Social Services.

Safeguarding must respect the autonomy and independence of individuals as well as their right to family life. In the context of the Human Rights Act, Article 8 Lord Justice Munby, speaking about people who are vulnerable or incapacitated states:

The fundamental point is that public authority decision-making must engage appropriately and meaningfully both with P and P's partner, relatives and carers. The State's obligations under Article 8 are not merely substantive; they are also procedural. Those affected must be allowed to participate effectively in the decision-making process. It is simply unacceptable – and an actionable breach of Article 8 – for adult social care to decide, without reference to P and their carers, what is to be done and then merely tell them – to "share" with them – the decision.

3. When and How to Apply 'Making Safeguarding Personal'

People cannot make decisions about their lives unless they know what the options are and what the implications of those options may be. They also need the chance to consider the options carefully. They can feel disempowered (and possibly damaged) by the safeguarding intervention unless they know what is happening and the choices they have. Therefore 'Making Safeguarding Personal' needs to be applied at every stage of safeguarding adults.

This means you need to ensure that:

- Advice about advocacy is provided at the very start of the enquiry and arrangements made for an independent advocate to represent and support the individual where he/she would have substantial difficulty in being involved in the process and where there is no other suitable person to represent and support them. Consideration must be given to appointing an Independent Capacity Advocate (ICA) where an individual lacks capacity and it is alleged that he/she has been abused or neglected by another person, or he/she is abusing or has abused another person;

- Safeguarding enquiries can proceed before the appointment of the advocate – but one must be appointed as soon as possible;

- The person at the centre of the enquiry and/or their advocate is fully involved from the outset;

- That the pace and locations of meetings are guided by the individual's needs and circumstances, lifestyle and choices;

- Accessible information and advice are readily available;

- The views and wishes/desired outcomes of the person/their advocate are understood and addressed.

- The person and their advocate are made aware of a range of possible options/outcomes from an intervention;

- Support is provided to help people make decisions where appropriate;

- The person and/ or advocate agrees that their views and wishes can be shared proportionately with other professionals that are involved in the care and care planning of that individual (for example health and care providers). The person should be informed when information is to be shared and for what reason. Only relevant information will be shared. Note: professionals should ensure that case notes and records are transparent and can be shared with the individual and or advocate as required.

4. The Importance of Meeting the Person Concerned and/or their Advocate

'Making Safeguarding Personal' puts the person involved in the safeguarding enquiry at its very heart. Therefore fully understanding their thoughts and wishes is vital if the outcome is to be successful. As practitioners you should aim to develop a positive rapport with the individual and/or their advocate from the very beginning. Provide support to the individual, and as importantly, to the advocate in their role of representing the individual. Support should be welcomed, valued and help practitioners to gain trust and confidence.

One way to build rapport is to have purposeful, respectful, face-to-face meetings. Make sure when you are setting these up that you check out where and when is best for the people you are meeting. Also, if the meeting is taking place away from their home, that the access and facilities in the chosen venue are suitable and that your conversations are strictly private and cannot be overheard.

Let the person and/or their advocate set the pace. Don't rush them or lead them. Match the type of language that they use so that you neither confuse and overwhelm them, nor are seen as patronising. Listen carefully and show empathy throughout.

Remember to go into any meeting with the viewpoint that the person involved in the safeguarding enquiry and/or their advocate know the situation best and that taking their wishes, feelings, and beliefs into account is paramount. Also, that any decisions that are made, require the individual and/or their advocates participation. It is vital therefore that any meetings are managed in a way that ensures that this happens.

At the end of the safeguarding enquiry it is important that conversations take place that provide the individual and/or their advocate with good information and feedback.

5. Conversations to Find out What the Person/ their Advocate Wants to Happen

'Making Safeguarding Personal' is about talking through with people the options they have and what they want to do about their situation. Asking the questions "What do you want to happen?", "What's important to you?", "Is there anything that you don't want to happen?" should take place fairly early on in the conversation.

Doing this is likely to result in more in-depth work at the early stage and better decision making regarding safeguarding activity.

It is extremely useful to help identify people's priorities and what needs to happen to make them feel safe. Encouraging them to record these can be very worthwhile, as they then have their own record to reflect upon or refer back to later.

The person's priorities and subsequent actions should also be added to case notes.

Examples of the type of outcomes or conclusions that people may want are:

- To be and feel safer;

- To maintain a key relationship;

- To have help to recover;

- To have access to justice or an apology, or to know that disciplinary or other action has been taken;

- To know that this won't happen to anyone else;

- To maintain control over the situation;

- To have exercised choice;

- To be involved in making decisions;

- To be able to protect themselves in future;

- To know where to get help.

Conversations may lead the individual and/or their advocate to identify other desired outcomes that are not included in this list. This list is not prescriptive. Recognise the person's identified outcomes, in their own words.

'Making Safeguarding Personal' is about empowering and involving people who are involved in safeguarding enquiries so that they feel that the process has been a positive one for them, and has led to the results that they wanted at the outset or they are happy with the conclusion.

In order to monitor progress and effectiveness and indeed know when outcomes have been achieved it is essential that the initial desired outcomes are recorded along with any information that demonstrates why they are important to the individual. Then as the safeguarding enquiry progresses it is necessary for these outcomes to be reviewed on an on-going basis. This:

- Helps keep the person at the centre of the enquiry;

- Keeps everyone on track with what needs to be done;

- Assists the person and/or their advocate to review the risks and rethink the outcomes if required;

- Enables agreement that an outcome has been met as far as is possible;

- Clarifies the end of the safeguarding support.

Whenever a review is carried out, the new information needs to be captured on the case notes in order to show what has changed, what was agreed and what has been achieved.

People's outcomes may change as time elapses. This is Ok.

6. Recording and Evaluating the Desired Outcomes at the Different Stages of the Intervention

As the safeguarding enquiry progresses, practitioners need to be able to demonstrate that their work is effective.

After the initial outcomes have been agreed, it is important that at any subsequent meetings/ discussions about how things are progressing towards achievement of the outcomes take place and are recorded. This ensures that everyone knows whether things are 'on track' or if additional action needs to take place. It also confirms who will carry out the action and by when.

Once it has been agreed that the outcomes have been met as far as possible, and the process is at an end, feedback needs to be gathered from the person involved and/or their advocate about their experience of the Safeguarding support.

The information from the feedback should be uploaded onto case notes. Only by knowing this will all practitioners, local teams and the Safeguarding Partnership Board be able to understand the impact that this approach to safeguarding is having on the individuals involved and whether good outcomes have been achieved. Whilst we may strive to meet people's outcomes – sometimes this will not be achievable.

7. Additional Things to Consider

- Consider the support in place for people following meetings. Particularly lone family members and family members who have not been invited to the meeting and may feel excluded;

- Consider any stigma the participant or family member may feel and how to deal with this;

- Consideration where possible for the same people from all agencies and professionals to remain consistent in meetings and throughout the process, including the chair. The person and/or their advocate to be informed of key people's absence and the reasons why;

- Consider the clarity of information given to an individual or their supporter when more than one statutory agency is involved – the roles and responsibilities of each agency;

- Consider what written safeguarding information may be required to help the person understand and stay in control;

- Consider the environment and location of the safeguarding meeting and for the individual and/or their advocate to be involved in this decision;

- Consider where a meeting is held in two parts, it may be more appropriate for the individual and/or their advocate to be the first in the room rather than enter a room of professionals;

- Consider person-centred safeguarding meetings as best practice with the right people being present for the contribution they can make, rather than a reflection of professional roles e.g. ensuring the person is asked who they would like to attend, not duplicating roles and reducing the possibility of participants feeling overwhelmed.

The person's desired outcome may not always be achievable (for example if they wish for the police to prosecute, but there is no evidence that a crime has been committed.) In these circumstances, the person's view should still be recorded, but practitioners need to talk to them about why their desired outcome may not be achievable. This is Ok.

Conversations with the person should continue and achievable outcomes can be discussed and negotiated on a continuum.

If a person with capacity refuses a safeguarding intervention, this should normally be respected however, just because an adult initially refuses the offer of assistance the person should still receive continued support. The situation should be monitored and the individual informed that she or he can take up the offer of assistance at any time. Where a criminal offence may have taken place or where there may be a significant risk of harm to a third party, the concern should be raised, and the person informed of your reason for doing so without their express consent. If, for example, there may be an abusive adult in a position of authority in relation to other adults at risk, it may be appropriate to breach confidentiality and disclose information to an appropriate authority, the SAT, Police, JCC.

7. 'Making Safeguarding Personal' – Example Case Studies from Other Areas

Case Study 1

Joyce had been experiencing issues with her neighbour. He had been asking her to lend him money. However Joyce said she didn't want 'anything to be done' as he was 'very kind' and was visiting her 2-3 times a week. She didn't want him to stop visiting her. Following further discussion between the practitioner and Joyce, where different options for responding were considered, Joyce said that she would like to speak with her neighbour on her own, but she wasn't sure how to start the conversation. The practitioner provided Joyce with some coaching about how she might start the conversation and what she wanted to get out of it. Joyce then felt able to talk with her neighbour about the issues. Whilst the neighbour was initially defensive, saying that he would never pressurise her to give him money, after a day or so he reflected on what Joyce had said to him and he visited her again to apologise for putting Joyce in the position where she didn't feel she could say no to his request. Although Joyce reports that her relationship with her neighbour is 'a bit fragile' since she talked to him he is still visiting her and hasn't asked her for money since she spoke with him.

Joyce felt able to talk about her experience of sight loss and how this had affected her confidence and self-esteem.

When a member of the safeguarding team met with Joyce to talk with her about her experience of safeguarding practice, she said that she felt she was listened to and that we wouldn't do anything unless she said we could.

Case Study 2

Sam has a moderate learning disability. She lives in a supported living shared house with minimal support.

There have been previous safeguarding referrals alleging sexual abuse of Sam by her boyfriend. These have been reported but no Police action has been taken to date. Sam has been assessed as having capacity to make decisions about her relationship. A wide range of agencies and professionals are involved with Sam. Sam wanted to remain with her boyfriend. She wanted him to treat her differently and for the professionals to help change his behaviour.

Professionals wanted to put in a range of protective measures to prevent the sexual relationship whilst the risk remained significant. Sam attended the safeguarding meetings enabling her to express to all professionals what she wanted and dismiss the outcomes being suggested by professionals. The outcomes Sam wanted to achieve were at the centre of the safeguarding intervention. Positive risk assessments were a useful tool both to share with other professionals (in showing what was important to Sam) and in continued work with her enabling her to recognise the risk posed by the relationship with her boyfriend alongside her initial wish to maintain the relationship. Her preferred outcomes were represented at all safeguarding meetings and revisited and reviewed.

During the safeguarding process Sam began to realise that her initial outcomes were not achievable. She began to understand that her initial outcomes were unrealistic and the extent of the risk was not safe for her. Sam realised that her boyfriend's behaviour towards her would not change and that professionals could not change his behaviour.

She was supported with this by intensive work from the agencies involved with her. Sam adapted the outcomes she wanted as she began to understand what was necessary to enable her to feel safe and minimise risk. She expressed a wish ultimately to leave her boyfriend. She set in place a long-term solution that she was happy with, to live in a new environment away from her boyfriend. Sam weighed up the risks and took the decision herself – with guidance and ongoing support from professionals.

Case Study 3

Mrs T is from time to time mentally unwell. She has been suffering with extreme depression and has been an inpatient within a local mental health unit. She has no immediate family but recently, as she has been unwell, some extended family members have visited her. They have heard that she has made a Will and the main beneficiary is a younger person who has been living in her property for several years paying a small amount of rent. The family members are also concerned about the "state of the house". They raised a safeguarding alert citing financial/material abuse and neglect at the hands of the "lodger" (although there is no indication that this person has caring responsibilities).

Mrs T was visited on the ward in relation to these concerns and although some discussion could take place, there was some lack of clarity and concerns that Mrs T was not capacitated. She understood that there was a lodger in the house and could name him, but not discuss the financial matters in any great detail.

She agreed for social services to visit the house to consider if there would be any need for assistance once she was discharged home. She was not able to discuss her Will or talk about the relationship between her and the lodger. It was not possible therefore at this time to conclude whether anything untoward was taking place. Mrs T was not well enough to participate in assessing the concerns raised or in making any decisions. The timescales set out within the policy and procedures for safeguarding adults' investigations were relaxed to allow time for Mrs T to recover and regain her capacity (which it was anticipated would "return" once she made a recovery). A visit to the house by the care coordinator took place, and no concerns regarding the neglect outlined by extended family were noted.

After three weeks Mrs T was able to discuss in detail the arrangements she had with the "lodger" and her views about her recent contact with extended family members. She talked fondly of the lodger and felt the contribution he made to the household budget was adequate and that he was good company. He also was very helpful to her with shopping, taking her out and carried out minor repairs to the property when necessary. The safeguarding adults' process was explained to Mrs T and she did not want any further action taken in this regard. However, she was supported to speak with her family who were informed of the outcome. They accepted this and the case was closed.

Here are some quotes from our reference group in Jersey:

'I would prefer someone talking to me, getting things out in the open, making sense of things at my pace'

'Please don't send me letters and minutes, my reading isn't all that'

'Please do not talk about me, you must include me – how will you know the facts if I'm not there in person'

'I don't like meetings; can we do this differently'

'I need my sister to be involved, she can remember and explain things when we're alone'

'My opinion is the main one – the one that really counts'

'Tell me in pictures, so I can fully understand'

'We suffer in silence – professionals do not listen to us properly'

'I am old school – face to face is much better than speaking on the phone'

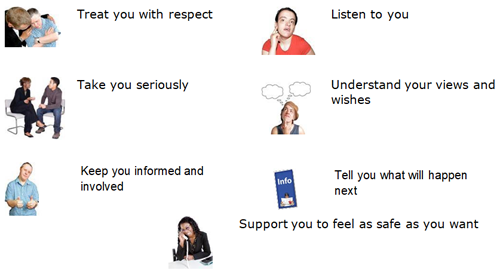

8. 'Making Safeguarding Personal' – Our promise to:

9. Outcomes the Person may Want to Achieve from Safeguarding?

Discuss and encourage the person to consider their top three outcomes and what is most important to them (in their own words).

"What do you want to happen?"

- I want the abuse to stop and to feel safer;

- I want to help protect myself in future;

- I want help to feel more confident;

- I want the abuser to stay away from me;

- I want to be involved in what happens next;

- I want people involved in my case to do what they say they will;

- I want the police to prosecute;

- I want any support available to me;

- Something else …………………………………………….